2 Pts What Animal Did Thomas Hunt Morgan Use To Study Heredity On?

Thomas Hunt Morgan and his legacy

by Edward B. Lewis

1995 Nobel Laureate in Physiology or Medicine

Thomas Hunt Morgan was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1933. The work for which the prize was awarded was completed over a 17-twelvemonth menses at Columbia University, commencing in 1910 with his discovery of the white-eyed mutation in the fruit wing, Drosophila.

Morgan received his Ph. D. degree in 1890 at Johns Hopkins University. He then went to Europe and is said to accept been much influenced by a stay at the Naples Marine Laboratory and contact at that place with A. Dohrn and H. Driesch. He learned the importance of pursuing an experimental, equally opposed to descriptive, approach to studying biology and in particular embryology, which was his principal interest early in his career. A useful account of Morgan's life and works has been given by 1000. Allen (ref. i).

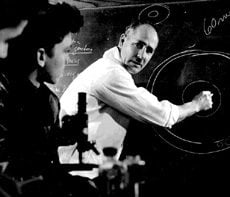

Thomas Hunt Morgan with fly drawings.

Courtesy of the Caltech Archives. © California Institute of Technology. All rights reserved. Commercial use or modification of this cloth is prohibited.

In 1928 he moved with several of his group to Pasadena, where he joined the faculty of the California Institute of Technology (or Caltech) and became the offset chairman of its Biology Division. What factors were responsible for the successes that Morgan and his students achieved at Columbia University and how did these factors conduct over to the Caltech era first under Morgan'south, and afterward G.W. Beadle'south leadership? It is user-friendly to consider 3 fourth dimension periods:

Morgan and the Columbia Period (1910 to 1928)

Morgan attracted extremely gifted students, in item, A.H. Sturtevant, C.B. Bridges, and H.J. Muller (Nobel Laureate, 1946). They were to discover a host of new laws of genetics, while working in the "Fly Room," in the Zoology Department at Columbia.

Throughout their careers Morgan and these students worked at the demote. The investigator must be on superlative of the research if he or she is to recognize unexpected findings when they occur. Sturtevant has stated that Morgan would oft annotate about experiments that led to quite unexpected results: "they [the flies] will fool you every time."

Morgan attracted funding for his research from the Carnegie Institution of Washington. That organization recognized the basic research grapheme of Morgan's work and supported research staff members in Morgan's group, such equally C.B. Bridges and Morgan'south artist, Edith Wallace, who was besides curator of stocks. The Carnegie grants required zero more an annual report from the investigators. Federal support had not still started and although universities were able to finance costs associated with pedagogy they were ordinarily unable to back up basic research.

C. Bridges, P. Reed, T.H. Morgan, A.H. Sturtevant, E.K. Wallace.

Courtesy of the Caltech Athenaeum. © California Institute of Technology. All rights reserved. Commercial use or modification of this material is prohibited.

During the Columbia menstruation Morgan was clearly in his prime. His way of doing science must have been of paramount importance. He was not afraid to challenge existing dogma. He had become dissatisfied, even skeptical, of the formalistic handling that genetics had taken in the flow between the rediscovery of Mendelism in 1901 and 1909. He ridiculed explanations of breeding results that postulated more and more than hereditary factors without any manner of determining what those factors were. He wanted to know what the physical ground of such factors might be. At that fourth dimension it was by and large causeless that chromosomes could not be the carriers of the genetic information. He wanted a suitable animal and chose Drosophila, because of its short life cycle, ease of culturing and high fecundity. Also, large numbers of flies could exist reared inexpensively — an of import gene during this menstruum when there were very few funds available to support basic research. Morgan was very thrifty when information technology came to purchasing laboratory equipment and supplies — but, according to Sturtevant, generous in providing fiscal help to his students. At the start of the piece of work hand lenses were used. But subsequently did Bridges introduce stereoscopic microscopes. Bridges too devised a standard agar-based culture medium. Prior to that, flies were simply reared on bananas. In addition, Bridges built the bones collection of mutant stocks, mapped nearly all of the genes and later, at Caltech, drew the definitive maps of the salivary gland chromosomes. His enormous research output may in part be attributed to his being a staff member of the Carnegie Foundation with consequent liberty from teaching and other academic obligations.

Morgan's start attempts to find tractable mutations to report were quite disappointing. Fortunately, he persevered and constitute the white-eyed wing1. This led to his discovery of sexual practice-linked inheritance and presently with the discovery of a second sex-linked mutant, rudimentary, he discovered crossing over.

H. Sturtevant in the Drosophila stock room of the Kerckhoff Laboratories.

Courtesy of the Caltech Archives. © California Establish of Engineering. All rights reserved. Commercial use or modification of this textile is prohibited.

Sturtevant (ref. 2) has described how chromosomes finally came to be identified as the carriers of the hereditary cloth. In a chat with Morgan in 1911 nigh the spatial relations of genes in the nucleus, Sturtevant, who was nevertheless an undergraduate, realized that the sex-linked factors might exist arranged in a linear order. He writes that he went home and spent the dark constructing a genetic map based on five sex-linked mutations that by then had been discovered. In 1912 Bridges and Sturtevant identified and mapped two groups of autosomal (not sexual practice-linked) factors and a third such group was identified by Muller in 1914. The four linkage groups correlated nicely with the four pairs of chromosomes that Drosophila was known to possess. Proof that this correlation was not adventitious came when Bridges used the results of irregular segregation of the sex chromosomes (or non-disjunction) to provide an elegant proof that the chromosomes are indeed the bearers of the hereditary factors or genes equally they are now known. Bridges published this proof in 1916 in the showtime paper of volume I of the journal Genetics.

Sturtevant often commented on Morgan's remarkable intuitive powers. Thus, Sturtevant describes how after explaining some puzzling results to Morgan, Morgan replied that information technology sounded like an inversion2. Sturtevant went on to provide critical evidence, purely from breeding results, that inversions do occur; it was but later that inversions were observed cytologically.

Information technology seems articulate that Morgan was not only a stimulating person but one who recognized good students, gave them liberty and infinite to work, and inspired them to make the leaps of imagination that are so important in advancing science.

Morgan and the Caltech Period (1928 to 1942)

Robert A. Millikan with cosmic ray equipment.

Courtesy of the Caltech Archives. © California Institute of Technology. All rights reserved. Commercial apply or modification of this textile is prohibited.

Morgan was invited past the astronomer, G.Due east. Hale, to chair a Biology Sectionalization at the California Constitute of Engineering science (Caltech). Hale had conceived the idea of creating Caltech some years earlier and had already recruited R.A. Millikan (Nobel Laureate in Physics, 1923) and A.A. Noyes to head the Physics and Chemistry Divisions, respectively. Co-ordinate to Sturtevant, Morgan told his group at Columbia of Unhurt's invitation and of how information technology was not possible to say no to Unhurt. Morgan accustomed and came to Caltech in 1928. He brought with him Sturtevant, who came as a full professor, Bridges, and T. Dobzhansky, who later became a full professor. In addition to Sturtevant and Dobzhansky, the genetics faculty consisted of E.G. Anderson and South. Emerson. J. Schultz, who similar Bridges was a staff fellow member of the Carnegie Establishment of Washington, participated in the educational activity of an avant-garde laboratory course in genetics.

During this 2nd period, many geneticists visited the Biological science Division for varying periods of fourth dimension. Those from foreign countries included D. Catcheside, B. Ephrussi, K. Mather, and J. Monod (1965 Nobel Laureate). Visiting professors included Muller and L.J. Stadler. B. McClintock (1983 Nobel Laureate) came every bit a National Research Fellow in the early 1930s.

Morgan was well known outside of the scientific community and attracted interesting people. Professor Norman Horowitz, who was a graduate student in the Biology Sectionalization during this menses, tells me that he remembers Morgan giving a tour of the Biology Partitioning to the well-known writer, H.1000. Wells.

Back (left to right): Wildman, Beadle, Lewis, Wiersma; continuing: Keighley, Sturtevant, Went, Haagen-Smit, Mitchell, Van Harreveld, Alles, Anderson; seated (back row): Borsook, Emerson; (front row): Dubnoff, Bonner, Tyler, Horowitz.

Courtesy of the Caltech Archives. © California Institute of Engineering science. All rights reserved. Commercial use or modification of this material is prohibited.

J.R. Goodstein (ref. 3) has described how the Rockefeller Foundation and private donors provided fiscal support to the Biology and other Divisions during this menses. Such assistance was essential at that time, since Caltech is a private institution and received no support from the state or the federal authorities.

Edward B. Lewis with Drosophila.

Courtesy of the Caltech Archives. © California Establish of Applied science. All rights reserved. Commercial use or modification of this textile is prohibited.

In the latter half of this period, Morgan returned to his interest in marine organisms and did not follow the newer developments in genetics. Instead it was largely Sturtevant who carried on the Morgan legacy as far every bit genetics was concerned. Sturtevant also allowed his graduate students considerable freedom to choose their thesis projects and to consult with him on those projects or indeed on whatever matter. I was fortunate to have been 1 such student, commencing in 1939. Sturtevant's door was ever open up to students and kinesthesia. I well think Morgan coming to Sturtevant'south office to discuss matters affecting the Division.

Sturtevant told us that the award of the Nobel Prize to Morgan in 1933 was an of import factor in elevating the prestige and status of the Biology Division at the Institute. At the time, the only other Nobel Laureate at Caltech was Millikan. From 1942 to 1946, the Partition was managed by a committee chaired by Sturtevant.

Beadle and the Caltech Period (1946 to 1961)

Beadle and Pauling with molecular model.

Courtesy of the Caltech Archives. © California Institute of Technology. All rights reserved. Commercial use or modification of this textile is prohibited.

In 1946, Sturtevant and Linus Pauling (who was awarded Nobel Prizes in Chemistry, 1954, and Peace, 1962) persuaded Beadle, who was then Professor of Biology at Stanford University, to become chairman of the Biology Division. Beadle carried on the Morgan tradition of strongly supporting bones inquiry and maintaining a stimulating intellectual atmosphere. During the early 1930s Beadle had been a National Enquiry Fellow in the Sectionalisation. He had collaborated with Sturtevant on a monumental written report of inversions and together they wrote a textbook of genetics. He had collaborated also during that time with Sterling Emerson, and with E.Thousand. Anderson. Beadle was clearly a function of the Morgan legacy.

Beadle in lab glaze.

George Beadle and B. Ephrussi using microscopes.

Both photos courtesy of the Caltech Archives. © California Institute of Engineering. All rights reserved. Commercial use or modification of this cloth is prohibited.

Beadle received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1958 for work carried out at Stanford University on the biochemical genetics of the staff of life mold, Neurospora. In his biographical memoir on Beadle, Horowitz (ref. four) describes how, while postdoctoral fellows in the Biology Division, Beadle and Ephrussi decided to pursue an early discovery by Sturtevant; namely, that a diffusible substance must be involved in the synthesis of the brown centre pigment of Drosophila. Sturtevant had shown that the vermilion centre color mutation is non-autonomously expressed in flies that are mosaic for the vermilion mutation and its wild-blazon allele. Beadle and Ephrussi designed at Caltech a set of experiments, involving transplantation of larval imaginal center discs, to written report the vermilion-plus hormone, as they chosen the diffusible substance. They carried out these experiments in Paris in Ephrussi's laboratory. They were able to show that another heart color gene, cinnabar, lacks a cinnabar-plus substance and that the wild-type vermilion and cinnabar genes control sequential steps in a biochemical pathway leading to the brown eye pigment. Beadle correctly realized that the fungus Neurospora would provide better genetic fabric for exploring such pathways. Beadle and Due east. Tatum (co-winner with Beadle of the Nobel Prize) and colleagues at Stanford were then successful in dissecting the biochemical pathways that are involved in the synthesis of vitamins and many amino acids in that organism. The Neurospora findings opened a new era, now known as molecular genetics.

During Beadle's tenure equally chairman, N.H. Horowitz, H.K. Mitchell, R.D. Owen, and R.S. Edgar were added to the faculty in genetics. [I had come as an instructor in 1946 before Beadle had arrived]. Horowitz and Mitchell had been associated with Beadle at Stanford and played major roles in developing the one-cistron i-enzyme hypothesis that led to the honour of the Nobel Prize to Beadle and Tatum.

Beadle was responsible for persuading Delbrück to render to Caltech every bit a full professor. Delbrück had not been offered an date at Caltech after his tenure in the Sectionalization in the 1930s as a post-doctoral fellow and had taken a faculty position at Vanderbilt Academy. Other appointments during Beadle's chairmanship that added strength in animal virology were R. Dulbecco (1975 Nobel Laureate), and M. Vogt. Howard Temin was ane of Dulbecco's graduate students and afterward a cowinner with Dulbecco of the Nobel Prize in 1975. R. Sperry (1981 Nobel Laureate) joined the kinesthesia every bit a total professor in 1954 and continued his work on carve up brains that he had begun at the University of Chicago.

R. Dulbecco, Yard. Beadle, 1000. Delbrück and H. Temin.

Courtesy of the Caltech Archives. © California Establish of Technology. All rights reserved. Commercial utilize or modification of this material is prohibited.

Basic research gradually became well supported financially by Federal Agencies commencing with the Part of Naval Inquiry, the Atomic Free energy Committee and finally by the National Institutes of Wellness and the National Science Foundation. Such back up was essential to obtain the personnel, equipment and supplies needed by the new fields of molecular and microbial genetics which flourished and indeed flowered during Beadle's chairmanship.

During this 3rd period at that place were many postdoctoral inquiry fellows in the Biology Segmentation, including Southward. Benzer (Crafoord Prize in 1993), who was a post-doctoral fellow in Delbrück's group from 1949 to 1951, and was later recruited in 1967 as full professor. J. Weigle was a visiting professor and a valuable member of the Delbrück grouping. At that place were visits by F. Jacob (Nobel Laureate, 1965) and J. Watson (Nobel Laureate, 1962). B. McClintock returned in 1946 for a curt visit, working with ane of the graduate students, Jessie Singleton, perfecting a method of analyzing the chromosomes of Neurospora. Interestingly, R. Feynman, Caltech professor of physics (Nobel Laureate in Physics, 1965), spent part of an academic year working with R. Edgar and other members of the Delbrück group.

George Beadle at blackboard.

Courtesy of the Caltech Archives. © California Institute of Technology. All rights reserved. Commercial apply or modification of this material is prohibited.

Beadle had remarkably versatile skills. He early abased his research on Neurospora in club to devote full time to existence chairman. He was very successful in finding donors to endow postdoctoral fellowships and new buildings. The fellowships were often used to support visits by strange scientists who otherwise would not take had been able to come to the Usa. Equally in the previous period, teaching loads were kept light and much teaching was conducted in the form of seminars and journal clubs. The biology kinesthesia was more often than not a harmonious group and students were allowed considerable freedom to choose their professors. As one of a number of measures of the success of this temper, the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to Professors Delbrück, Dulbecco and Sperry, as already noted, and in my instance as well, for work carried out in the Division under the leadership of Beadle.

George Beadle and students.

Courtesy of the Caltech Archives. © California Found of Applied science. All rights reserved. Commercial use or modification of this cloth is prohibited.

Notes

i. Mutant and Wild Fly

Photo kindly provided by Nils Ringertz.

Photo kindly provided by Nils Ringertz.

2. Inversion

References

1. Allen, K., Thomas Hunt Morgan, pp. 1-447, Princeton University Press, Princeton, North.J. (1978).

two. Sturtevant, A.H., A History of Genetics, pp. 1-165, Harper and Rowe, New York (1965).

3. Goodstein, J.R., Millikan'southward School, W. W. Norton and Co., New York. pp. ane-318 (1991).

4. Horowitz, N.H. Biographical Memoirs, vol. 59, pp. 26-52, National Academy Printing, Washington, D. C. (1990).

Beginning published 20 April 1998

Back to tiptop

Nobel Prizes 2021

Thirteen laureates were awarded a Nobel Prize in 2021, for achievements that take conferred the greatest do good to humankind.

Their work and discoveries range from the Earth's climate and our sense of touch to efforts to safeguard freedom of expression.

See them all presented hither.

Source: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1933/morgan/article/

Posted by: franklinsart1949.blogspot.com

0 Response to "2 Pts What Animal Did Thomas Hunt Morgan Use To Study Heredity On?"

Post a Comment